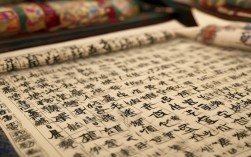

Chinese idioms, known as chengyu, are compact expressions rich in history and meaning. Each one carries a story, often from ancient texts or folklore, offering lessons that remain relevant today. For global readers, understanding these idioms opens a window into Chinese culture and philosophy. Here are some well-known chengyu with their English equivalents and origins.

画蛇添足 (Huà Shé Tiān Zú) – "Drawing Legs on a Snake"

Meaning: Overdoing something unnecessary, ruining a good thing by adding superfluous details.

Story: During the Warring States period, a man rewarded his servants with a pot of wine. To decide who would drink it, they agreed to draw snakes—the fastest artist would win. One man finished first but arrogantly added legs to his snake. Another pointed out snakes don’t have legs, disqualifying him. The lesson? Unnecessary actions can backfire.

English Equivalent: "Gilding the lily" (from Shakespeare’s King John), meaning to over-embellish.

守株待兔 (Shǒu Zhū Dài Tù) – "Waiting by the Stump for a Hare"

Meaning: Relying on luck rather than effort.

Story: A farmer once saw a hare crash into a tree stump and die. Instead of working, he waited daily for another hare to do the same. Of course, it never happened, and his fields lay barren.

English Equivalent: "Waiting for lightning to strike twice," implying unrealistic expectations.

亡羊补牢 (Wáng Yáng Bǔ Láo) – "Mending the Pen After Losing Sheep"

Meaning: Fixing a mistake before it worsens.

Story: A shepherd noticed a missing sheep but ignored the broken pen. The next day, more sheep escaped. Only then did he repair the pen, preventing further loss.

English Equivalent: "Better late than never."

对牛弹琴 (Duì Niú Tán Qín) – "Playing the Lute to a Cow"

Meaning: Wasting effort on an unappreciative audience.

Story: A musician played elegant tunes for a cow, hoping to soothe it. The cow ignored him, chewing grass indifferently.

English Equivalent: "Casting pearls before swine" (from the Bible).

井底之蛙 (Jǐng Dǐ Zhī Wā) – "The Frog at the Bottom of a Well"

Meaning: Limited perspective due to narrow experience.

Story: A frog living in a well bragged about its "vast" world. When a turtle described the ocean, the frog couldn’t fathom it.

English Equivalent: "Seeing only through a keyhole."

狐假虎威 (Hú Jiǎ Hǔ Wēi) – "The Fox Borrows the Tiger’s Might"

Meaning: Using someone else’s power to intimidate.

Story: A fox tricked a tiger into walking behind it. Animals fled at the sight, fearing the tiger—not the fox.

English Equivalent: "Riding on someone’s coattails."

杯弓蛇影 (Bēi Gōng Shé Yǐng) – "Seeing a Snake in a Wine Cup"

Meaning: Unnecessary paranoia.

Story: A man saw a "snake" in his wine, fell ill, and later realized it was just the bow’s reflection.

English Equivalent: "Jumping at shadows."

塞翁失马 (Sài Wēng Shī Mǎ) – "The Old Man Who Lost His Horse"

Meaning: Misfortune may bring hidden blessings.

Story: When a man’s horse ran away, neighbors called it bad luck. Later, the horse returned with wild horses, bringing wealth. Then his son broke a leg riding one—but this spared him from conscription in a deadly war.

English Equivalent: "Every cloud has a silver lining."

一箭双雕 (Yī Jiàn Shuāng Diāo) – "One Arrow, Two Eagles"

Meaning: Achieving two goals with one action.

Story: A skilled archer shot an arrow through two eagles mid-flight.

English Equivalent: "Killing two birds with one stone."

掩耳盗铃 (Yǎn Ěr Dào Líng) – "Covering Ears to Steal a Bell"

Meaning: Self-deception.

Story: A thief covered his ears while stealing a bell, thinking others wouldn’t hear it ring.

English Equivalent: "Burying one’s head in the sand."

Why These Stories Matter

Chinese idioms distill centuries of wisdom into a few characters. For English speakers, they offer fresh perspectives on universal truths—caution against arrogance, the value of adaptability, or the illusion of control. By exploring these tales, we bridge cultures, finding common ground in shared human experiences.

Learning chengyu isn’t just about language; it’s about grasping the philosophy behind them. Whether you’re a student, traveler, or curious mind, these stories remind us that wisdom transcends borders.